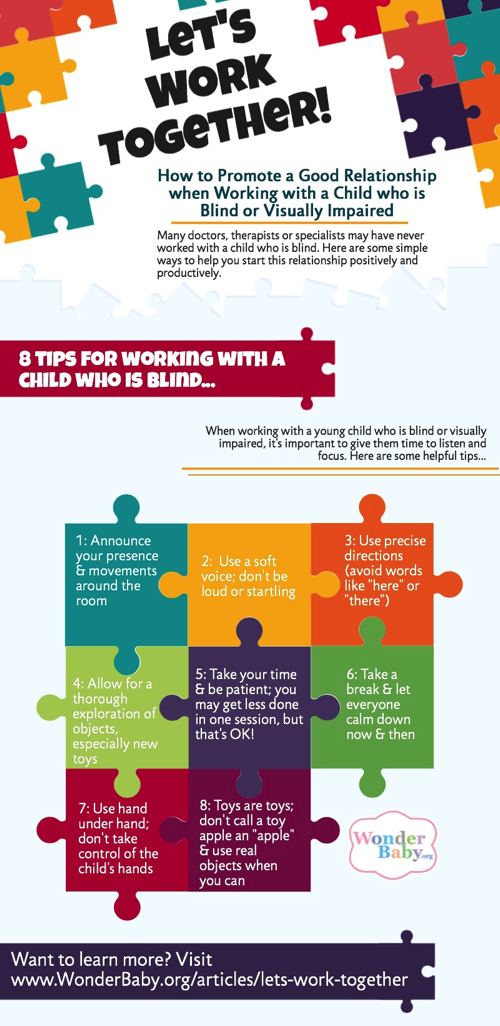

Let’s Work Together: 8 Tips for Working with a Child Who is Blind

Do you dread that weekly visit from your child’s physical therapist? Is a trip to the doctor’s office a nightmare? If your blind or visually impaired child spends most of their time around doctors and therapists kicking and screaming you may think there’s something wrong… and you’re probably right.

But chances are pretty good that it’s the doctor or the therapist who needs to shape up, not your kid!

Here’s a typical scene from a real-life encounter my son recently had with a pediatrician:

The doctor, a specialist who works with disabled children, wanted to know if my son would squeeze a noise-making toy when asked. She placed the toy on the table in front of my son, squeezed it, and said in a very sweet voice, “Now you squeeze the porcupine.”

My son was hesitant. What was that noise? What kind of thing is this? What’s a porcupine?

The doctor squeezed the toy again then gently reached for my son’s hand and placed it on the toy. She then made his hand squeeze the toy so that it would squeak.

My son quickly pulled his hand back and whined. The doctor tried once more and this time the response was an ear splitting cry.

“Well,” she said, “we know one thing for sure. He’s afraid of new toys.”

What went wrong here? I can tell you two things for certain: My son can squeeze noise-making toys and he is not afraid of new toys. So why didn’t he perform the way the doctor wanted him to? Why did the session end in tears?

As the parent of a blind child I know you can pick out many little problems in the above scene. The doctor labeled the toy a “porcupine” which has no meaning to my son and confused him; she held his hand and tried to make him perform a task he wasn’t ready to do; and she moved too quickly without letting my son first explore the toy and “see” it on his own terms. But, most importantly, I didn’t help the doctor interact with my son. I know him better than she does and I should have guided the session. But I wasn’t sure how to best approach the doctor. She was the expert, after all.

Many doctors and therapists, even the specialists, however, have had little to no contact with blind children, and most of what they do know about vision impairment was learned from a book. While books can be great places to start, nothing teaches you more than hands-on experience. Which means, at least when it comes to dealing with your child, you are the expert, not the doctor, and you need to remember that.

Also, your child is probably still too young to tell the doctor or therapist when they are uncomfortable. This means that you need to act as your child’s voice by telling your doctors and therapists how to behave around your child.

A good approach, and one that I’ve found to be very effective, is to set some ground rules from the beginning. You may want to just sit down with your doctor or therapist and talk about your child and how best to interact with them or you may want to write out a concise list of do’s and don’t’s that you can hand to them at your first meeting. Whichever method you are most comfortable with, you will need to figure out ahead of time what you want to say. Try thinking in your child’s voice. What would he or she say to the therapist? Here are some ideas to get you started:

- Always announce your presence and your movements about the room. I can’t see you coming or going and it can be very scary to suddenly find myself sitting next to a stranger.

- Use a soft voice. Even though it’s important to announce yourself, you should do so in a soft voice that isn’t loud and startling.

- Use precise directions. The words “here” and “there” convey very little meaning to me since I can’t see where you’re pointing. Try saying something more exact, like “by your left foot.”

- Let me “see” an object first. This is really important and often hard to remember. You’ll be bringing out lots of neat toys for me to play with but I’ll want to explore them thoroughly in my own way before I’m able to show you what I can do with them. Since I can’t see the toy visually, I’ll first need to touch, turn, and maybe even mouth the toy. This may take a little time, often several minutes. Please be patient.

- Take your time. I know we only have an hour or so to play, but I move at a different pace since I need to use my other senses besides vision to process what’s going on. Give me time to figure out what’s happening, to decide to move on to something different, or to celebrate an accomplishment. We might get to fewer things in one session, but that’s okay.

- Take a break. Too much information and input can easily over-stimulate me. Sometimes I just need to calm down and catch my breath.

- Let me remain in control of my hands. Since I can’t see, my hands often act as my eyes. It can be very uncomfortable for me to have my hands manipulated, especially without warning. If you want me to touch a toy, shake it or tap it so I know where it is or place it gently near my fingertips. If you want me to move my hands toward a toy a better approach may be to slowly guide my arm by the elbow rather than by the hands.

- Remember that toys are toys. Even though that toy is shaped like a duck, it isn’t a duck. It doesn’t have feathers, it doesn’t quack, and it isn’t alive. Plastic or stuffed toys may represent real-life objects, but they are really only toys. If you can’t see the representations, those connections are lost. Please refer to toys as toys so that I don’t become confused.

Be open about what your child needs and hopefully your doctor or therapist will also be open about how best to interact with them.

If you like the above list, you can download the file here and print it on your own computer. You will need Adobe Acrobat to read the file. Sometimes I find that colored paper gets a better response, so you may want to try printing it in color. Good luck!

Related Posts

Eye Conditions and Syndromes, Visual Impairment

Neuralink Announces Plans to Restore Sight to the Blind with Brain Chip

Elon Musk’s company Neuralink has announced plans to begin human trials of its new “Blindsight” brain chip by the end of 2025.

Visual Impairment

The Gift of Understanding: How a Young Child Helps His Blind Father Navigate Life

When a parent is blind, it’s natural for people to wonder how their sighted child will adapt. Will they struggle to understand their parent’s needs? Will they feel burdened by...

Braille and Literacy, Toys, Visual Impairment

24 Braille Toys for Kids Who are Blind

Everything from alphabet blocks to raised line coloring pages and activity books to puzzles to card and board games... and so much more! And it's all in braille ready for...